# 8.4 Constitutional Guidelines

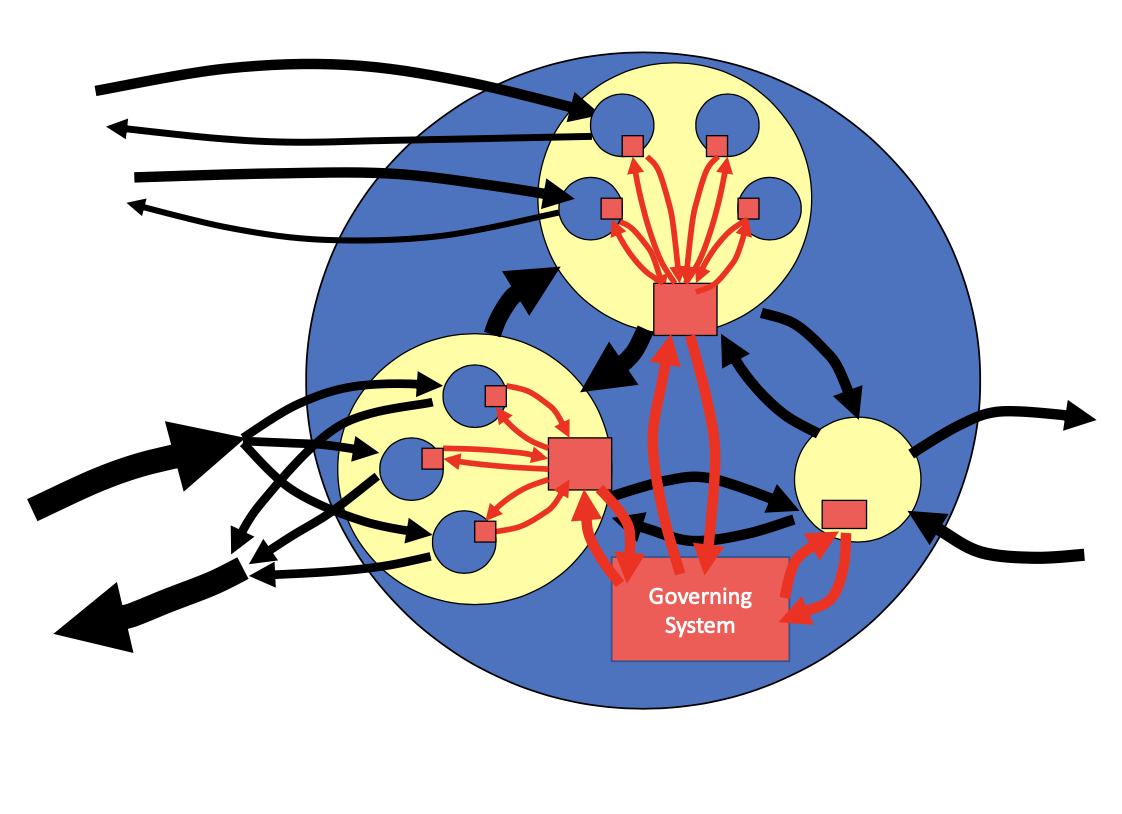

In Chapter 4 I explored the consequences of moving to modelling an organisation in a systemic way starting from considerations of holding steady in a changing environment and having to deal with both internal and external disturbances. This approach resulted in a layered fractal structure. That layered fractal structure is of course the reason for fixing on the word ‘community’ because it is a word which is essentially fractal in nature, in that it is used to describe a system in focus as is required for a systemic analysis. Figure 8.3 reproduces figure 4.11 now illustrating the layered structure of a community government and its relationships to its environment and to the sub- communities and sub-sub-communities.

Figure 8.5: The Layered Community Structure

Figure 8.5: The Layered Community Structure

Many governments have evolved to have a layered structure, but it has to be said that the relationship between the layers does not seem well understood. In the UK in 1977 a Scottish Member of the United Kingdom Parliament Tam Dalyell posed a question that is still a subject of controversy a generation on; what was dubbed the ‘West Lothian Question’. The question asks - Should Scottish Members of Parliament vote on 8 issues concerning only the governing of England? This is exactly the question of how adjacent levels of management should relate that was resolved in chapter 4, but I would like to set it out in this context in more detail.

The key to solving the West Lothian question is in finding a way for conflict to be avoided if there are two governments, with one whose domain of governance includes the other. Perhaps most importantly, if it is possible to find a principle or principles upon which the relationship between two overlapping levels of government can be constructed, then we can define the relationship between any two levels in a multi-level system. As was described in Chapter 5 all team games solve this problem. To recap in any team game there are a set of rules which apply to all the players taking part in a game, the metasystem. Within this agreed governance framework each team and its players have the freedom to play their game as they wish and take their own team decisions among themselves. The rules of any game give rights to players, ‘freedom to’ act and communicate in certain ways, but also provide constraints curtailing freedom, giving players ‘freedom from’ being on the receiving end of other particular acts and communications. A team can on its own account set higher standards of behaviour, but not lower, and they can certainly decide their own strategies of play. This relationship between the whole group rules (the framework which establishes the game) and the subgroup rules (the strategies that a team uses in taking part), and the way in which the two levels relate is an example of governance in the form needed to provide the answer to the West Lothian question.

The whole community government is concerned only with this whole group framework and the issues associated with its establishment and maintenance. In normal circumstances there can be no concern with internal matters of any sub-community, just as is the case for the sovereignty of nation states within international law. The key to understanding the relationship between two levels of government is that there must be restrictions on both the upper level and the lower level on what can be decided, what legislation can be put in place. There is inevitably a greater diversity of views across the larger group than across any sub-community. The area of agreement on a framework will of necessity be on a minimal set of agreed rights and constraints. The decisions of the whole community government must be restricted to those affecting only the whole community in constructing and maintaining this framework.

In the example of England and the whole of the United Kingdom, issues concerning England only should be considered and decided by a body or bodies governing England: an English parliament or appropriate regional parliaments. Each of these must be sovereign alongside the Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish parliaments within the common United Kingdom framework set by a United Kingdom constitution. With this principle as the starting point in designing a governing structure, the problems we face in that design are enormously simplified because the principle can be applied to distinguish the functions of any two adjacent levels in a multi-level governing system.

However, in adopting this principle we consign to the medieval history books the principle of sovereignty as it is currently defined and used. At present the government of a larger community can interfere arbitrarily in any way at any time it deems necessary in the smaller contained community. In the past sovereign kings and queens 9 have not been renowned for their open, informed, fair and just decision making. The notion that there is a hierarchy in which the higher echelons can interfere at will in the lower echelons must be abandoned. Powerful and unconstrained actions in the upper echelons of a hierarchy certainly do not give rise to open, informed, fair and just governance, but more likely give rise to moral and financial corruption. In my experience it seems that those in the higher levels of a hierarchy often seek to perpetuate their own position and power rather than govern as representatives of the population.

What do we gain from defining the relationship between levels in this way? At one extreme of decision making it is clearly a fantasy that a king, a queen, a pope, a prime minister, or a chief executive officer can be infallible, and all-seeing. All human beings have a limited capacity to understand the enormous complexity of the world in which we live, whatever their role in it. They do not have the necessary variety of potential command. The collective knowledge of the governing body of the larger community containing the smaller is limited. Even a few members representing a city in a national government living for a large part of their time at some distance from that city can never act collectively as intelligently as a local city government body of many more people in every day touch. So in structuring any governing system, it is as essential to prevent interference from those who are not affected and do not understand, as it is to give access to those who are affected and do understand.

Narrowing the domain of decision making in this way, will focus the minds of those involved in the whole community government on a range of issues and roles which can be better encompassed by a human brain, so increasing both the effectiveness and efficiency of governing structures. This at least maximises the possibility that in any government the people affected and the people who understand are both involved as far as possible in the decision making processes which affect them. This approach to structuring will tend to decentralise decision making, since unless it can be argued that a decision affects the whole community group, it cannot be considered by the government of the whole community group.