# A House of Representatives

The problem we have in making a comparison between the government of ancient Athens and modern communities is that from my definition communities can be very large, up to and including the community of humans on planet earth. In Athens every citizen could be involved in governmental decision-making, but in a nation state with a typical population in the millions or tens of millions this is not feasible. In the modern situation it seems to be generally accepted that ‘representative democracy’ is the ideal to aim for. Instead of every adult being involved we choose representatives, creating a body to take decisions on our behalf. The meaning of ‘represent’ in this context according to the dictionary (e.g. Chambers 1998) is ‘to stand for’. The purpose of this ‘standing for’ is that the representatives take governing decisions on behalf of the people of the community as a whole, to the benefit of the whole community. If representatives are going to stand for the people of the community as a whole, then they must carry with them to their task, as far as possible, the rich variety of background, culture, and attitudes of all the people of the community which they represent. Culture varies from place to place, from organisation to organisation, and from profession to profession; a governing system must capture as far as possible this variety. If representatives are taking decisions standing for a community of people then there must be as far as possible an alignment with, and understanding of, this rich variety in that controlling body. Only then can they stand for the population in deciding what is appropriate, and what is not, making those decisions to the benefit of the community as a whole.

But then the question arises as to the ability and desirability of a small number of people to represent a large number in this way. What is then at issue is the quality of those decisions since all citizens are not involved. The fractal constitutional structure explored in the last section does alleviate this problem restricting the range of decision making at any level of community, but it does not entirely solve the problem. The implications of the Conant-Ashby Theorem enjoin us to seek to establish in the 11 controlling governmental system the best possible model of the community and its needs and problems. How could this be done?

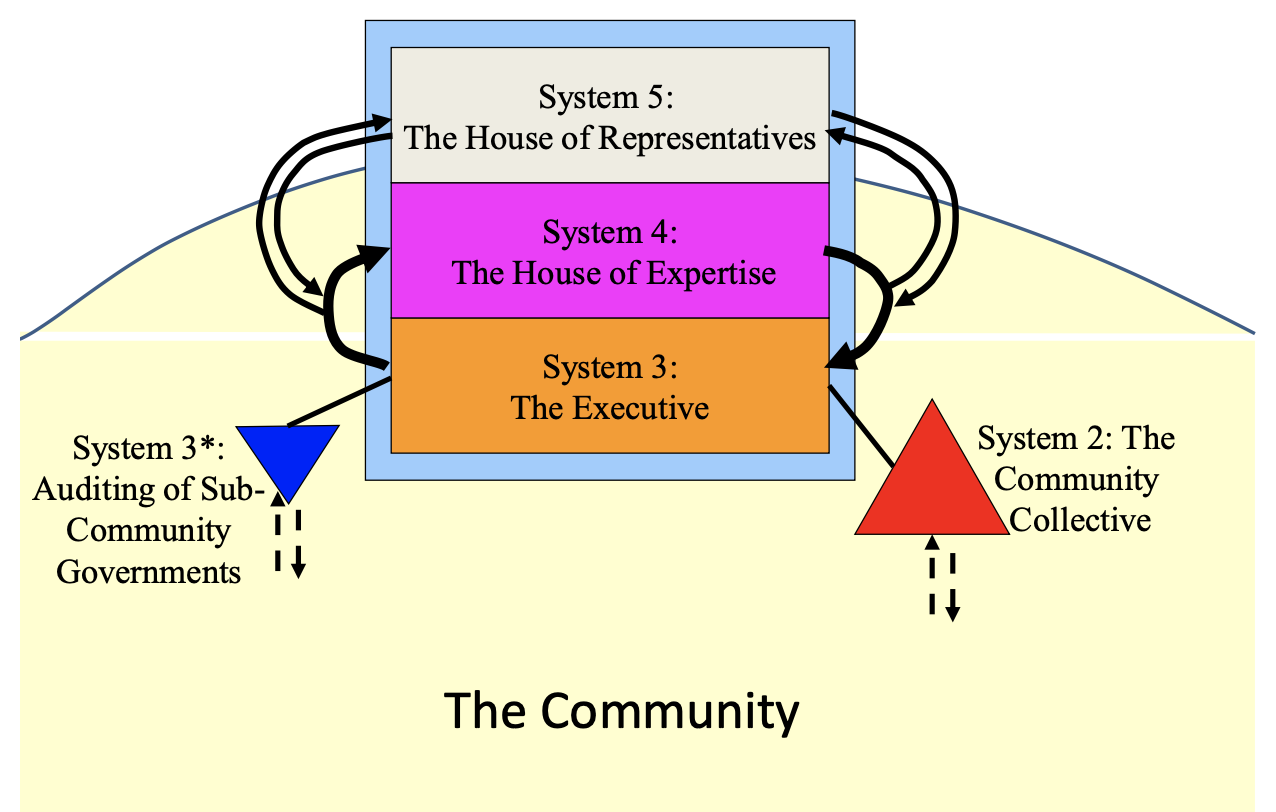

The systemic control system proposed by Beer, the Viable System Model (VSM), explored in the previous chapters, and illustrated in Figure 8.6, is divided into five sub- systems, System 5 is to embody the being of the whole system, and is the guardian of the identity and purpose of the system as was described in section 4.7. An animal is itself, its being developed by coevolution with the environment within which it lives. In the modern world a community has the opportunity to develop an understanding of its being and decide how it wishes to relate to the environment. In a direct democracy this is the responsibility of the whole collective of the citizens, in a representative democracy the responsibility of a House of Representatives, standing for the whole collective of the citizens. As guardian of the identity and purpose a House of Representatives’ function is to decide on what is appropriate and what is not in proposals it receives and make decisions standing for the people of that whole community, but most importantly, the fractal point, it can only make decisions which apply to the whole community. I explored examples of what might be the identity and purpose of a community in section 8.3 at the beginning of this chapter.

Figure 8.6: Community governing systems

Figure 8.6: Community governing systems

It is essential that there is understanding in that body of the rich variety of knowledge, understanding, and perspective in the community. Any democratic government therefore by design consists of groups of people representing their community who come from different backgrounds having differing perspectives on the complex situations they face, that they must come to an understanding of, and come to decisions about. The decision making process of democracy is necessarily through inclusive discussion, which requires developing agreed models of complex situations as discussed in Chapter 6. This is not at all the way our current governing systems are structured. It is more usual for governments to strip out the variety of perspectives, UK political parties are typical in that the choosing of parliamentary candidates to stand for election as 12 ‘representatives’ has been decided in large part centrally to fit with a particular political view. This is done often even without the candidate having any experience of the constituency concerned; a sure way to achieve incompetent governing. To achieve competent governing it is necessary to maintain an ongoing feedback loop between a House of Representatives and its community to ensure evolution with the community, and to counter misinformation and misunderstanding. To achieve this I would suggest also that frequent changes of representative are necessary to counter the possibilities of groupthink within the House of Representatives; representation cannot be a permanent career.